MUDTUPU: The Dying Folk Art of Odisha

In the quiet hills of interior Odisha,

where dusty trails wind past forgotten hamlets and life moves to the rhythm of

survival, an ancient, unsettling act continues to unfold. It's called Mudtupu—a ritual in which a man buries his head in the ground, not in shame or defeat,

but in desperate hope. Hope for a few coins. A fistful of rice. A day’s meal.

This isn’t a metaphor. For the Mundapota

Kela community, Mudtupu is real. It’s performance. It’s endurance. It’s art.

But above all, it’s survival.

A

Community Left Behind

The Mundapota Kela are a denotified

tribe, believed to have migrated decades ago from Andhra Pradesh’s Rayalaseema

region. Today, they live across parts of Odisha and Andhra, scattered across

remote villages and forest edges—places where roads fade, services vanish,

and identities are invisible.

They live in makeshift huts built with

mud, thatch, plastic, and palm leaves, usually on government land — land

they’ve occupied for generations but don’t legally own. Most have voter ID

cards. A few hold ration or job cards. But crucially, they lack land pattas and

caste certificates—the golden keys to government benefits.

Many identify as Scheduled Caste, using

surnames like "Sikari." But without proof, the state doesn’t

recognize them. Their children are denied scholarships. Their elders can’t

claim pensions. Officials still label them as nomads, even though they’ve lived

in the same place for over four decades.

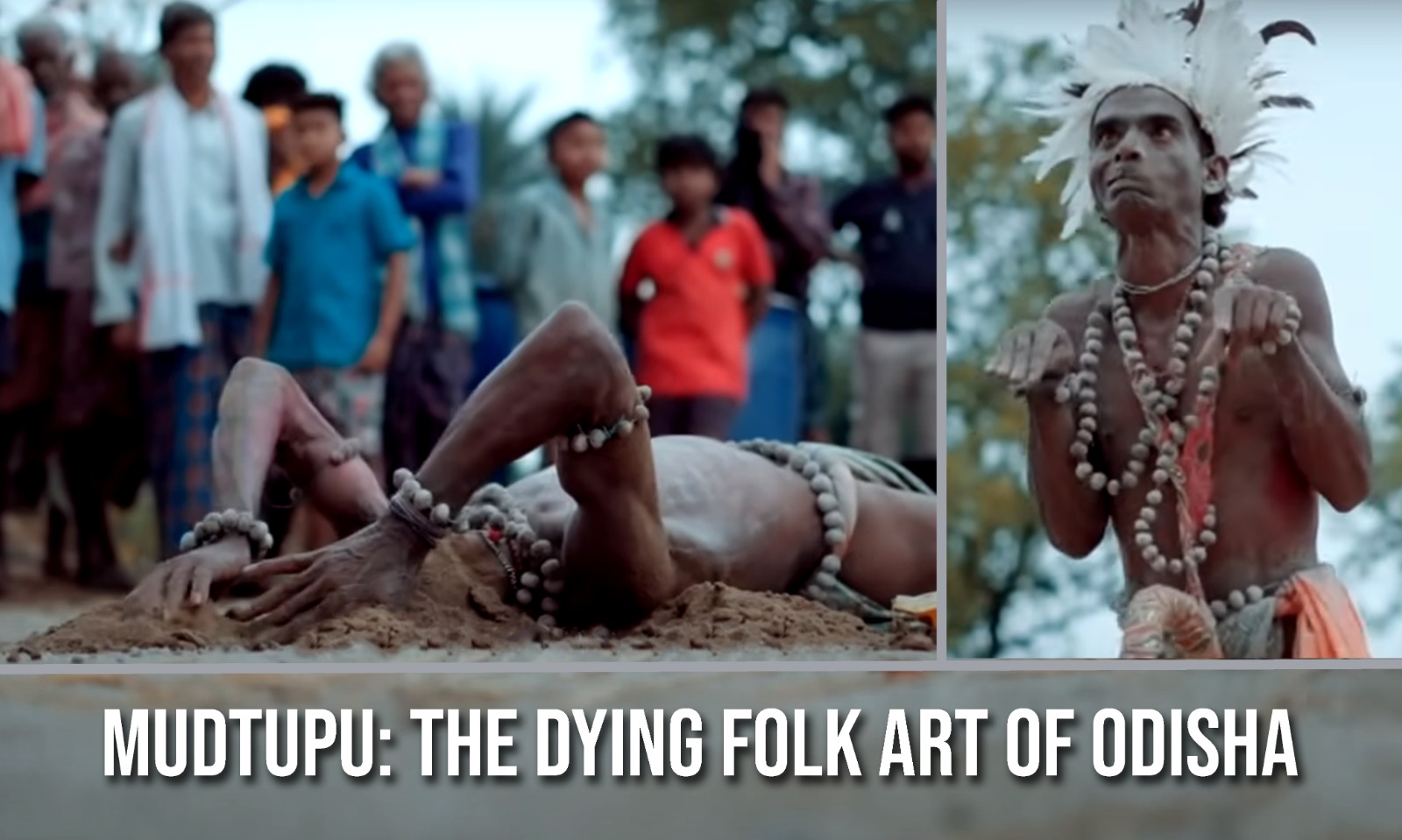

Mudtupu:

When Art Meets Desperation

The performance begins in a village

square. The man, dressed in rags and strapped with a makeshift horse frame,

dances in circles — a folk tradition called Ghoda Nacha. His wife beats a drum

to gather a crowd, while barefoot children twirl beside them.

Then comes the climax — he lies flat on

the ground, digs a shallow pit, and buries his head in the soil. For minutes,

he lies still, breath held, face unseen. The crowd gasps. Coins clink into a

bowl. Someone drops some rice. The wife continues drumming, occasionally

appealing for alms.

It’s a chilling act — one part

endurance, one part theatre, all wrapped in quiet pain. The community calls it

tradition. But let’s call it what it is: a ritual of survival.

Fading

Applause, Shrinking Crowds

Once, Mudtupu drew attention and

modest earnings. But now, fewer people pause to watch. Entertainment has

shifted to smartphones, and curiosity has faded. The performer is no longer met

with awe, but with indifference. “No one cares anymore,” says a woman from a nearby

village. Her husband once performed these acts, but passers-by would barely

notice. Today, she weaves brooms and mats to sell at the weekly market—a

livelihood that, at the very least, offers some return.

Like her, many in the community are

seeking alternative means of survival—crafting mats, working as agricultural

labourers, or gathering forest produce like honey. But these jobs are seasonal

and unreliable. On most days, there’s little work—and hunger remains a

constant companion.

Life

Without Basics

In the hills of Daspalla block, where

many Mundapota Kela families live, there are no proper roads. No electricity.

No health centres. No piped water. Women and children spend hours each day

walking miles to fetch water under the blazing sun. They live in isolation —

not just geographically, but socially.

They come down from the hills only once

a week, to attend the haat (weekly market) and buy essentials like salt and

kerosene. It’s a routine shaped by exclusion.

The

COVID Collapse

Then came COVID-19. Lockdowns shut down

markets. Public gatherings came to a halt. Performances vanished. The few

rupees they could scrape from the streets disappeared overnight. The government

provided some relief — a few kilos of rice, a one-off cash benefit. But for a community without documents,

even that was not guaranteed.

Begging became harder, more shameful.

And yet, it remained their only option.

A

Stigma Carried for Generations

History, too, has been unkind. In 1871,

the British branded several tribal and nomadic groups as "criminal

tribes" — including the Mundapota Kela. The stigma stuck. Even after

India’s independence and the repeal of the Criminal Tribes Act in 1952, little

changed. The 2008 Balakrishna Ranke Commission noted that denotified tribes

like this one continue to suffer from deep-rooted prejudice and neglect.

Excluded from both the Scheduled Caste

and Scheduled Tribe lists, Denotified and Nomadic Tribes (DNTs) still fall

through the cracks of India’s welfare net. They remain uncounted, unrecognised,

and unheard.

Promises

and Pitfalls

There is some movement. Local officials

in Daspalla say they are working to provide pensions, subsidised rice, and

drinking water through tube wells. It’s a step forward. But what’s truly needed

is systemic inclusion — legal identity, land rights, education, health access,

and above all, respect.

The Indian Constitution promises

equality — regardless of caste, creed, or livelihood. Yet, for the Mundapota

Kela, those rights remain on paper.

More

Than a Performance, A Plea

Mudtupu is not just a dying folk art. It

is a silent scream. A symbol of resilience. A cultural act that hides a

humanitarian crisis.

As India celebrates its 75th year of independence and hails its growth on global stages, let’s also look underground — to those who still bury their heads in soil just to eat. Their stories matter. Their traditions matter. And their dignity matters.

Let’s not just preserve their art.

Let’s restore their humanity.

It’s time we stop applauding the spectacle… and start acknowledging the struggle.